King Abdullah I, the first ruler of the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (later Jordan), had significant ambitions for territorial expansion, including control over parts of Palestine. His vision was tied to a broader "Greater Syria Plan," which aimed to unite Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine under a Hashemite dynasty, potentially with himself as king.

After World War I, the British Mandate for Palestine (1920–1948) was established, incorporating the Balfour Declaration’s promise of a "national home for the Jewish people" while also committing to Arab self-determination, and in 1921, Britain created the Emirate of Transjordan, placing Abdullah as its ruler. The territory east of the Jordan River was separated from the area designated for the Jewish national home, limiting Jewish settlement to western Palestine.

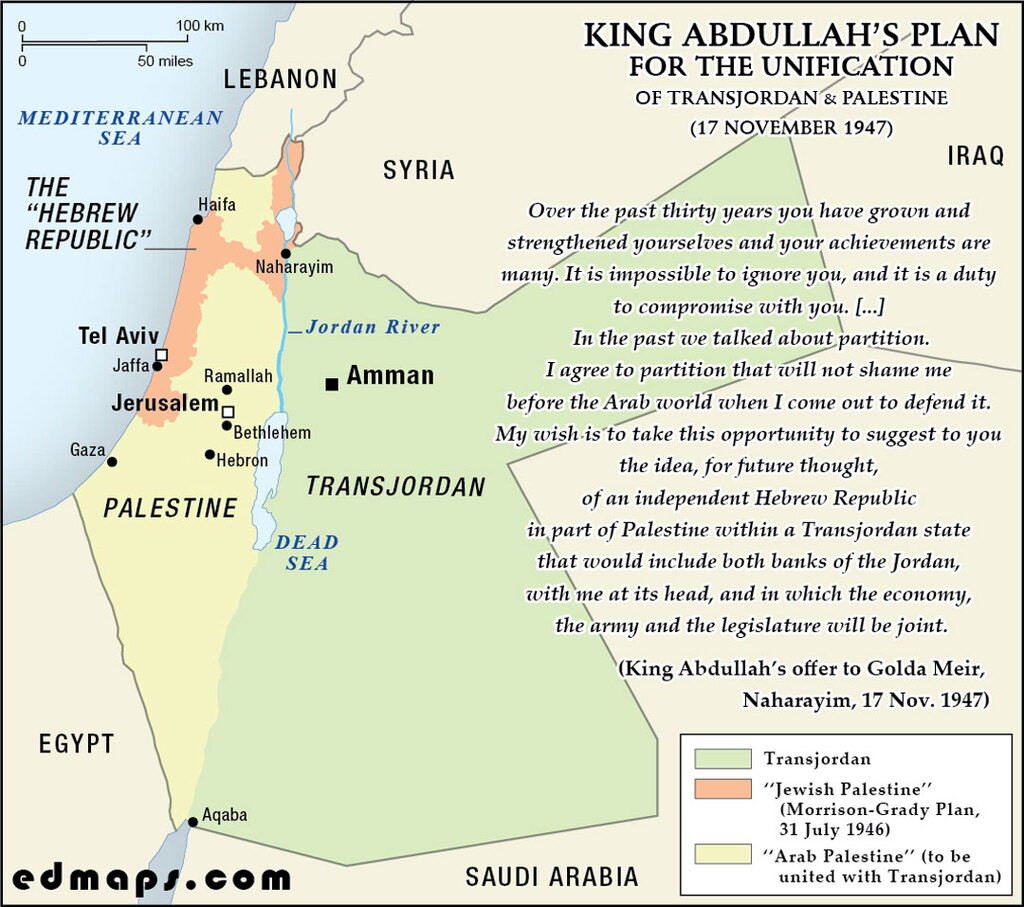

Abdullah engaged in secret talks with Zionist leaders, notably Golda Meir, in 1947–1948, to avoid conflict and negotiate territorial arrangements. In a November 1947 meeting, Abdullah proposed an autonomous ''Hebrew republic'' within a Hashemite kingdom, suggesting that Jews could have representation in his parliament without immediate statehood, but Golda Meir rejected this, insisting on the UN Partition Plan’s provision for a Jewish state.

The 1947 United Nations partition plan for Palestine, which proposed dividing the territory into separate Jewish and Arab states, was not the only solution being discussed at this critical juncture in Middle Eastern history. King Abdullah I of Transjordan offered a radically different vision—one that would have created an autonomous "Hebrew republic" within a larger Arab kingdom rather than independent Jewish statehood. His alternative proposal, though ultimately rejected, represented a unique diplomatic attempt to resolve the Palestinian question through accommodation rather than partition, and reflected his broader regional ambitions for Hashemite expansion across the Levant.

Abdullah's proposal emerged from the context of his "Greater Syria Plan," an ambitious vision to unite Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine under Hashemite rule, with himself as the unifying monarch. This territorial expansion strategy was not merely opportunistic but represented a coherent political philosophy that sought to recreate historical Syrian unity under modern Hashemite leadership.

The backdrop of Abdullah's proposal was shaped by decades of British mandate politics. Following World War I, the British Mandate for Palestine had attempted to balance the conflicting promises of the Balfour Declaration—supporting a Jewish national home—with commitments to Arab self-determination. When Britain established the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921 and installed Abdullah as its ruler, they effectively separated the territory east of the Jordan River from areas designated for Jewish settlement, confining the latter to western Palestine.

Abdullah's diplomatic approach contrasted sharply with the confrontational stance adopted by many Arab leaders. Rather than rejecting any Jewish presence outright, he engaged in secret negotiations with Zionist leaders, most notably Golda Meir, during the crucial period of 1947-1948. These clandestine meetings reflected his pragmatic understanding that accommodation rather than conflict might better serve regional stability and his own territorial ambitions.

In November 1947, Abdullah presented his alternative vision during a pivotal meeting with Meir. His proposal was remarkably innovative for its time: instead of the UN's partition plan creating separate Jewish and Arab states, he suggested establishing an autonomous "Hebrew republic" within a larger Hashemite kingdom. This arrangement would grant Jews parliamentary representation and significant self-governance while avoiding the immediate creation of an independent Jewish state.

Abdullah's rationale was both strategic and temporal. "Why are you in such a hurry to proclaim your state? Why don't you wait a few years?" he reportedly asked Meir. His proposal envisioned a gradual process whereby he would "take over the whole country," presumably through negotiated agreements rather than military conquest, and then provide Jews with meaningful political representation within his expanded kingdom.

However, this alternative vision foundered on fundamental disagreements about sovereignty and timing. Golda Meir firmly rejected Abdullah's proposal, insisting on the UN Partition Plan's provision for immediate Jewish statehood. The Zionist leadership was unwilling to trade the promise of sovereignty for representation within an Arab-dominated kingdom, regardless of the autonomy offered.

Abdullah's proposal represented a fascinating "what-if" moment in Middle Eastern history—a potential path toward coexistence that might have avoided decades of conflict, yet one that ultimately proved incompatible with both Jewish aspirations for statehood and Arab nationalist rejection of any Jewish political entity in Palestine.